The “Sackback Status Symbol” Project:

Making a Gown for Penelope Home of Paxton House

Penelope Home was the daughter of a plantation owner in the West Indies. She married Ninian Home in the 1760s and they purchased Paxton House in the Scottish Borders from Ninian’s uncle in 1773. The only portrait that Paxton House has of Penelope shows her as just a tiny figure in the corner of a watercolour, but even that small glimpse reveals that she was a follower of fashion.

Paxton House also holds a gown from the 1770s (later altered) that appears to have originally been a long sackback gown similar to those Penelope doubtless wore in that time. It’s a style that was fashionable in Paris and London through the middle of the eighteenth century. These gowns had loose box pleats falling from the shoulders at the back, which allowed air to circulate around the body. When made up in cotton or linen, sackback gowns suited the humid climate of Grenada and Mustique in the Caribbean, where Penelope and Ninian owned plantations growing sugar and cotton — and hundreds of enslaved Africans.

Adam Callander, A View of (probably) Paraclete Estate, Grenada, 1789, Paxton House Trust, Accession No. 84P

By the time of their deaths in the mid-1790s, the Homes had taken on massive amounts of debt to fund their lifestyle, which included the commissioning of fine bespoke furniture from London-based cabinet makers Thomas Chippendale & Son, wearing fashionable clothes and throwing lavish parties. These debts rested entirely on profits made by their Caribbean plantations on the back of enslaved labour.

The Sackback Status Symbol project contributes to Paxton House’s

ongoing mission to represent women’s history more fully at Paxton.

In 2022, a special exhibition opened at Paxton House, titled “Parallel Lives, Worlds Apart: from sugar plantations in Grenada to life at Court, and other stories from the costume at Paxton House”. This exhibition explores Paxton House’s historical slavery-related collections, connecting with 21st century lives in African, Caribbean and other minority diaspora communities. The exhibition interprets British, African and Caribbean History onsite at Paxton House in new temporary, permanent, and online exhibitions and dovetails with funding that has further enabled the conservation, cataloguing, photography and display of more objects — including costume — in Paxton’s outstanding collections

As part of this project, Paxton House has been commissioning object research and the making of reconstructed garments by students on the University of Glasgow’s Dress and Textile Histories postgraduate degree program, for the purpose of representing named individuals — male and female, free and enslaved — connected with Paxton House and associated estates.

In April 2023, Cait Burk and I (as the latest cohort of students involved with this project) introduced visual and physical representation of Paxton House mistress and enslaver, Penelope Home, by presenting the making of a long sackback gown of the type that she most likely wore in the Caribbean. Over the course of one week, we demonstrated how 18th century mantuamakers made such gowns, while wearing comfortable period “undress” costume ourselves.

The event’s grand finale on Friday afternoon with Cait modelling the completed gown brought the past to life as she moved through spaces that Penelope inhabited, wearing a gown like Penelope wore. The completed gown then went on display in the Dining Room of Paxton House, a domestic space which Penelope commanded as mistress of the house, as well as a hostess within elite society living in the Scottish Borders, in Edinburgh and indeed as a British plantation owner in the Caribbean.

Project Video

Using photos and short bits of footage shot on mobile phones by staff, volunteers and visitors, I compiled a video capturing the highlights of our event as a way to record our work.

This has now been published in two parts on the Paxton House website. Here is the entire video.

Exhibition curator, Fiona Salvesen Murrell, and I wrote the following essays for the project.

These may be published on the Paxton House website in the future.

The work of a mantua-maker by Rebecca Olds

Dressmakers in the 18th century were called “mantua-makers”. This name came about in the late 17th century when there was a huge change in how women’s dresses were being made: no longer as a structured garment but as a loose flowing gown worn over separate, structured undergarments. This new style of dress was invented in France. In England, it was called a mantua, which probably derives from the French term “manteau” referring to the cut of a man’s coat, which the earliest forms of this dress resembled. In Scottish documents we often see the word written as “manto”, which gives us a pretty clear idea of how Scots were pronouncing the word, at least at first.

Over time through the 18th century, many styles of dresses were developed that were no longer much like the original mantuas, but the name “mantua-maker” stuck for the women (and they were nearly always women) making all these styles. Mantua-making was a separate garment-making trade from tailoring. Learning this trade meant serving an apprenticeship lasting several years – sometimes as many as 7 years but in Scotland it seems 3-4 years was fairly typical.

Once trained, a capable mantua-maker could, on her own, make a sack gown like the one you will see being made in this video, in about 15 hours. The working day for 18th century tradespeople started at dawn and ended at dusk. So in the summer, this gown could be made in just one day. In the winter, with the shorter daylight hours, a mantua-maker would need at least 2 days to finish and, in the north of Scotland, possibly even a third day. If she was working with a repeat client, she might be able to finish in less time if she did not need to do any fittings. Ideally, however, she preferred to cut the lining fabrics for each gown right on her customer, using her customer's body as we today might use a dressmaker's or tailor's dummy, cutting the fabrics into the right shapes, in the right sizes and proportions, to ensure a good fit. Linings could be cut in less than 10 minutes! Then the customer was free to go about her own business while the gown was being made up. The mantua-maker would deliver the completed garment to the customer's doorstep, with the bill for her labour tucked into the parcel.

When placing an order for a new gown, the customer would already have purchased the fabrics. The usual business model was that the mantua-maker supplied skill and labour, not materials. Labour costs varied widely between cities and rural areas, and in different parts of the UK, but the cost was low in proportion to materials. In the case of a fine gown made of costly fabric, the mantua-maker's bill might represent less than 10% of the total cost. For a more common workaday gown made of, for example, a sturdy linen, the cost ratio of labour to fabrics might be closer to 1:1, 50% for each.

Research at Paxton has revealed one mantua-maker connected with the estate. Frank Home, younger brother to Ninian Home who owned Paxton from 1773-1795, managed a plantation in Dominica in which he owned a half share. Before his death in 1779, Frank fathered a daughter, Jean, mostly likely with a Black or mixed-race woman. Jean was brought to Scotland, living under the care of guardians in Irvine. Her existence was only known to Ninian Home, until he told his brother George in the early 1790s. By c.1795-96, Jean was living in Edinburgh being supported by George Home while she trained to become a mantua-maker. Unfortunately, we do not know whether she completed her training and, if she did, where she worked and whether she was able to support herself in this trade.

The search for the perfect fabric by Fiona Salvesen Murrell

I first went about searching for fabric for this dress to be made in 2021/22 as I hoped to include a replica sackback gown within the ‘Parallel Lives, Worlds Apart; from Sugar plantations in Grenada, to life at Court’ exhibition, based upon the one sack back gown in Paxton's collection. The brocaded silk 1770s gown in the Trust's collection was altered sometime around the 1840s and is unfortunately too fragile to display.

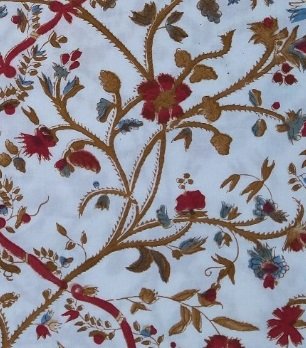

I sought advice from experts in the field. A plain satin dress had been recommended, but it was unclear whether this would be still worn in the 1770s in the Caribbean British Colonies, where cotton was cooler in the warm, humid climate of Grenada where Penelope and her husband Ninian Home lived extensively. Eventually, after many hours searching for a fabric pattern that was of the correct period, I found this handmade, hand-blocked replica 1770s cotton fabric with a trailing floral design. The small original fabric surviving sample is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and was imported into the Colonies there in the 1770s. The maker of the replica fabric extrapolated the missing repeat pattern sections to create new carved wooden blocks from which to print.

Exports of printed cotton from Britian and France circulated across the colonies and so it was felt this was the most appropriate fabric that was available to purchase, supported by grant funding from the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund.

‘Pandora’ or fashion doll,

made by Stefan Romero for Paxton House, 2021.

Textile fragment, 1770s,

Museum of Fine Arts Boston,

Accession No. 98.1823

Nicolas Arnoult (c.1645-1725), La Couturier, engraving,

Recueil de modes, Vol. 3,

Bibliotheque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr)

18th Century Reproduction "American Autumn"

Hand Block Print, by Peas Projects (https://www.peasprojects.com/)

Stefan Romero, a previous placement student from the Dress and Textile Histories degree course at the University of Glasgow, created the 'Pandora' or fashion doll, which is on display in the ‘Caribbean Connections, Slavery, and Paxton House’ exhibition. These dolls were used by tailors and mantua-makers to show the latest fashions in miniature to their prospective clients and were easy to transport to different centres and colonies to allow clients to commission new clothing. In this way, when Penelope Home was not in Scotland or London, she could see what the latest fashions were and buy the fabric she liked and have it made up into a stunning dress.

In stark contrast, the enslaved African people who worked on the plantations that Penelope and Ninian Home co-owned, were issued with cloth and clothing once a year. This was of rough, coarse linen and cotton. Handmade replica examples of these are on display in the Drawing Room and Library at Paxton as part of the current exhibition. These would become threadbare through hard labour.

The archives have revealed that some of the enslaved people at the Homes’ Waltham plantation in Grenada in the early 19th century grew enough surplus crops on their allotment style gardens to sell at market.* John Fairbairn, the estate manager, described to George Home in 1815 that the goods they were able to buy included ‘clothes, fine clothes’, parasols, gold rings and earrings, which were borrowed by other enslaved and free people for festivities, but this is likely to have been the exception to the rule (National Records of Scotland, ref: GD267/5/7/1). We don't know if the enslaved people in the 1770s had the opportunity to sell any surplus food at market.

*The enslaved people had to grow most of their own food, supplemented by imported goods such as salted fish and occasionally salted beef - but the cheapest cuts possible - heart and skirts of beef, which, enhanced with spices and long cooking, might have been more palatable.

Fiona’s photos and videos of Cait wearing the finished gown at the end of our week animates Penelope’s historical presence in her 1770s Scottish home.

The completed gown is currently on display in the Dining Room at Paxton House.

|nterpretative label next to the gown in the Dining Room. Photos Rebecca Olds 2023.